Dit artikel is heel bruikbaar voor mijn onderzoek om aan te tonen dat MKM een grote invloed kan hebben op lichte muziek en daarmee op mainstream doelgroep. De Beatles konden door de experimentele technieken van Stockhausen uitgroeien van een ‘stelletje brutale langharigen’ tot de band die de wereld veroverden met nummers als ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ en ‘I Am the Walrus’.

The Beatles’ Revolution 9 brought experimental music to a global audience, but their radio soundworld wouldn’t have been possible without Stockhausen’s ‘music of the whole world’

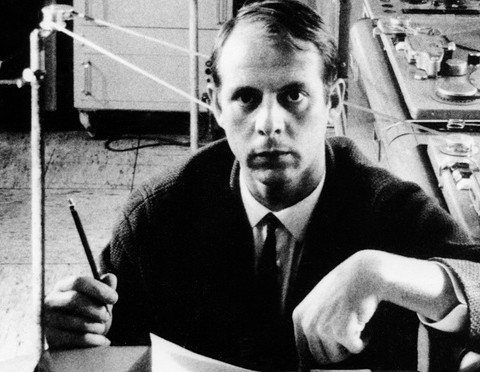

The German avant-garde composer, Karlheinz Stockhausen, listened to the radio a lot when he was a boy. He was born in 1928 when radio had become available to all and, when he was an infant, he discovered that he could immediately play on the piano any music he’d heard emanating from the crackling loudspeaker: an early indication of his incredible musical gift.

Fast forward to the 1960s. Stockhausen had found fame in the underground counter-cultural world of experimental arts. He’d made several pieces of electronic music that had been broadcast by radio stations around the globe, including the BBC. But these were not pieces played on pop music stations; they were initially known only to the followers of the avant garde: those who read cut-up novels, collected LPs of musique concrète and attended performances of experimental theatre, happenings, expanded cinema and psychedelic all‑nighters in hippy hangouts.

At this time, many more mainstream bands were exploring the possibilities of the recording studio. In the three years between 1964 and 1967 pop music changed more radically than it had in all the years since its inception in the 1950s. The Beatles went from being a bunch of cheeky moptops to a band working with tape loops and sound collages with tracks such as “Tomorrow Never Knows”, “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “I Am the Walrus”. The techniques used to create these soundworlds had been developed years before by composers like Stockhausen.

In 1967 he made a two-hour, four‑channel electronic composition called Hymnen (Anthems). It is an expansive, sonic landscape based on national anthems and other audio material from around the world. It also utilises the sounds of shortwave radio – “shortwave salad” as Stockhausen called it – the bleeps and fizz of atmospherics, the nebulous worlds between the stations, the hum and crackle of planet Earth. In conversation with Stockhausen, in 2001, I asked him about his fascination with shortwave. Why did he use it so much? He turned his palms upwards, shrugged his shoulders and replied “Instant electronic music.” And he’s correct: turning the tuning dial on an analogue radio produces a plethora of electronic sounds from the ether.

Hymnen is formed into four “regions” with “centres” that focus on different countries. The national anthems from those countries are heard in fragments, sometimes chopped up and sometimes electronically modulated making them sound as if they are being beamed from a distant galaxy. The first region begins with shortwave scramble from which, at one point, the words “United Nations” emerge. A fizzling recording of the French anthem competes for attention, and a mysterious character, the croupier, is introduced. He addresses us: “Faites vôtre jeu, Messieurs, Dames, s’il vous plaît”. Then, after a spin of the wheel, he intones “Neuf … the nine. Neuf … the nine” several times. All compellingly strange.

Great clangorous metallic chords introduce the second region and shredded anthems spin in space. There are recordings of crowds which transform into ducks that quack the Marseillaise. The British anthem floats away into morse code-like bleeps.

In the third region the Russian national anthem has been synthesised with electronic tones – an incredibly slow, laborious process back in 1966/67. It’s slowed almost to a standstill so we hear a drawn-out, shimmering, spectrum that changes with the anthem’s harmonies. This region has a live orchestral part that is rarely performed, but the London Sinfonietta gave an amazing rendition of it at the Royal Festival Hall early last month and BBC Radio 3 captured it all.

The fourth region is the strangest and darkest of all. The Swiss anthem glides between the four speakers as if sung by alien invaders in a flying saucer. Juddering tape feedback leads into muffled, indecipherable loops; voices call in a huge empty room; magic names are yelled into nightmare spaces: Turid, Naçar, Iri, Maka. The croupier appears again – “Faites vôtre jeu, Messieurs, Dames, s’il vous plait” – and after skittering fragments of many anthems, it all ends with a recording of Stockhausen inhaling and exhaling: “the breathing of the world”.

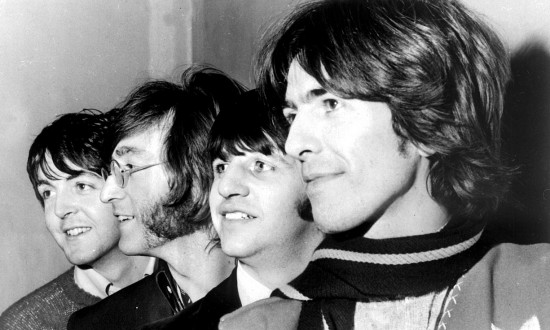

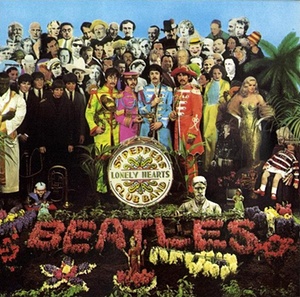

Only a few months after Stockhausen completed Hymnen, the Beatles were working on their White Album. In June 1968, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, with a little help from George Harrison, made what Beatles writer Ian MacDonald described as “the world’s most widely distributed avant-garde artefact”: “Revolution 9”. The band had acknowledged Stockhausen’s work by including him in the gathering on the cover of Sgt Pepper’s. Lennon had telephoned him a few times and a meeting was planned. There are strong connections between Hymnen and Revolution 9: the intoning of the number nine, recordings of waves of noisy crowds, the calling of magic names – Lennon’s and Harrison’s magic names are popular ballroom dances, “the Watusi” and “the Twist”, along with random snippets probably from a newspaper: “economically viable”, “industrial output”, “financial imbalance”. Both Hymnen and Revolution 9 were recorded using a four-track tape machine, the cutting-edge audio technology of the time. This eight-minute collage presents a snapshot of the end of the 60s and its presence on a Beatles LP brought the avant garde into millions of homes.

Hymnen launches Radio 3’s New Year New Music series on 1 January. bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06sb9lj. Sockhausen is Radio 3’s Composer of the Week on 4-8 January.