Bij de eerste indruk wordt ik gezien de grafische interface van de partituur al erg blij van dit filmpje. Het project was onderdeel van het Philips paviljoen op de wereldtentoonstelling in Brussel in 1958. Het betreft een multimediale samenwerking tussen Xenakis, Corbusier, en componist Varese.

link naar opname Poème Electronique: refmovie

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5a62bF50oIA

Mensen komen hier naar binnen en komen hier de voorstelling in, als een soort processie. Maakte de voorstelling mee van klank, kleur en licht. Het zijn archaische beelden, bijna reliefachtig. De relatie tussen de beeldenwereld van LeCorbusier en Varèse is dat Varèse exact hetzelfde deed met geluid. Je hoorde uitgesneden klanken die op de rand staan van het herkenbare. Zo’n klank verschijnt, je kunt denken dat het een kind is dat huilt, of je hoort een schreeuw of Gregoriaans gezang, maar het is zo kort dat het een uitsnede is. Het is geen lopend verhaal.

Poème électronique (English Translation: “Electronic Poem”) is an 8-minute piece of electronic music by composer Edgard Varèse, written for the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. The Philips corporation commissioned Le Corbusier to design the pavilion, which was intended as a showcase of their engineering progress. Le Corbusier came up with the title Poème électronique, saying he wanted to create a “poem in a bottle”. Varèse composed the piece with the intention of creating a liberation between sounds and as a result uses noises not usually considered “musical” throughout the piece.

Original performance

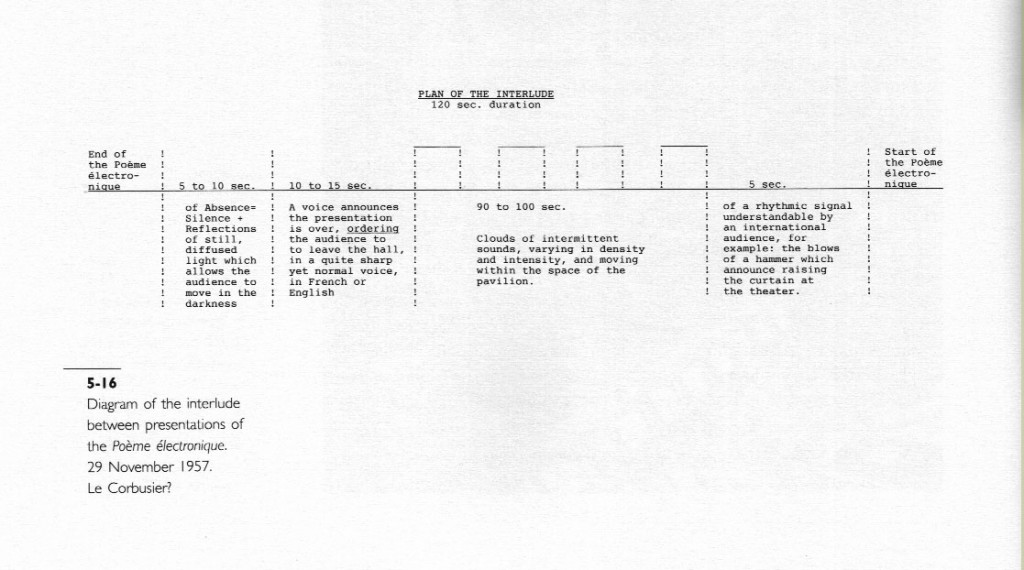

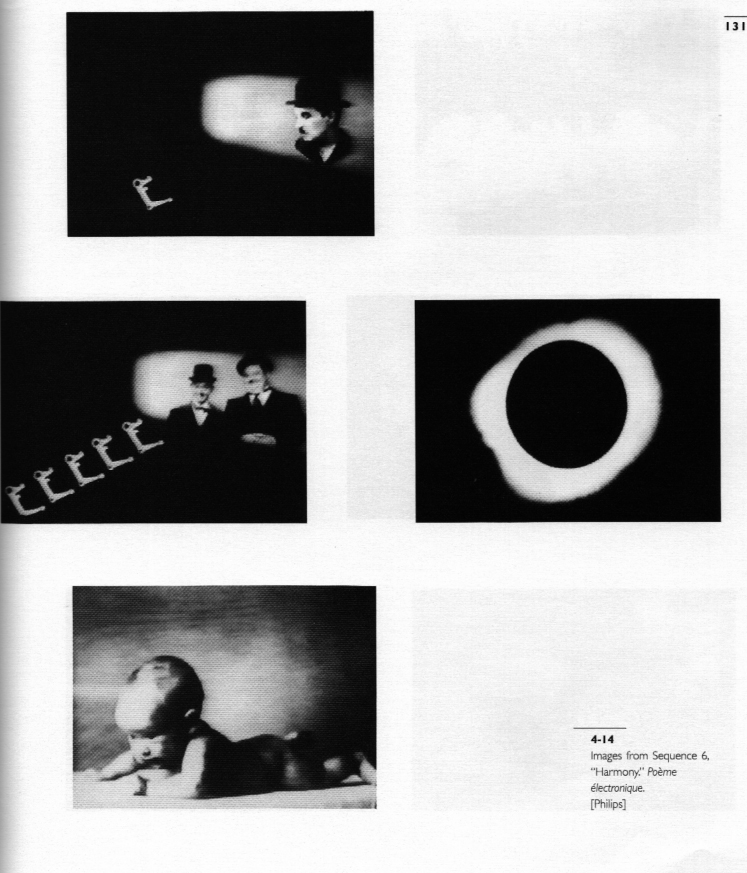

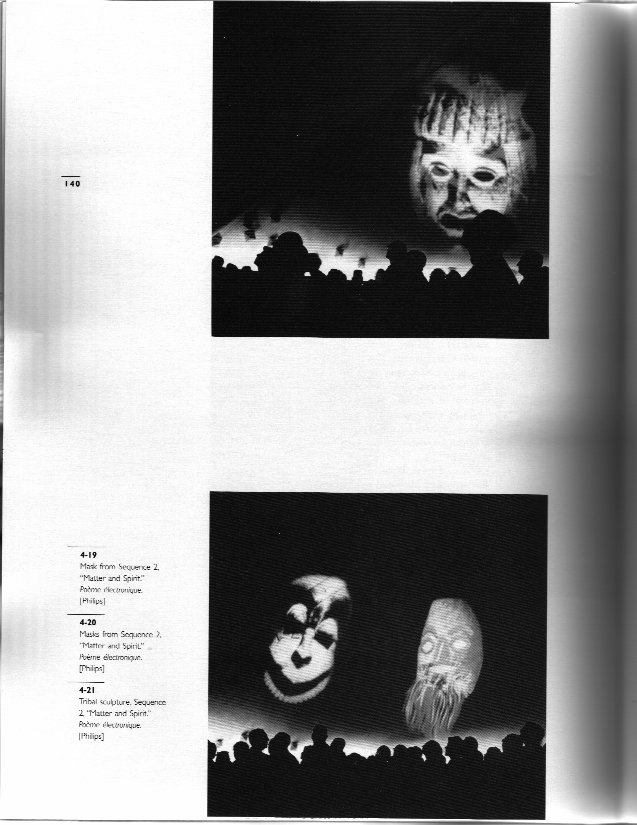

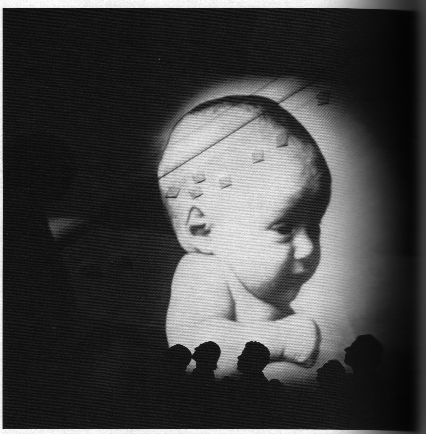

The pavilion was shaped like a stomach, with a narrow entrance and exit on either side of a large central space. As the audience entered and exited the pavilion, the electronic composition Concret PH by Iannis Xenakis (who also acted as Le Corbusier’s architectural assistant for the pavilion’s design) was heard. Poème électronique was synchronized to a film of black and white photographs selected by Le Corbusier which touched on vague themes of human existence. Le Corbusier’s original concept called for a pause in the film while his voice was heard, speaking directly to the audience. However, Varèse objected to the idea that Le Corbusier’s voice would be played over his composition, and the idea was abandoned.

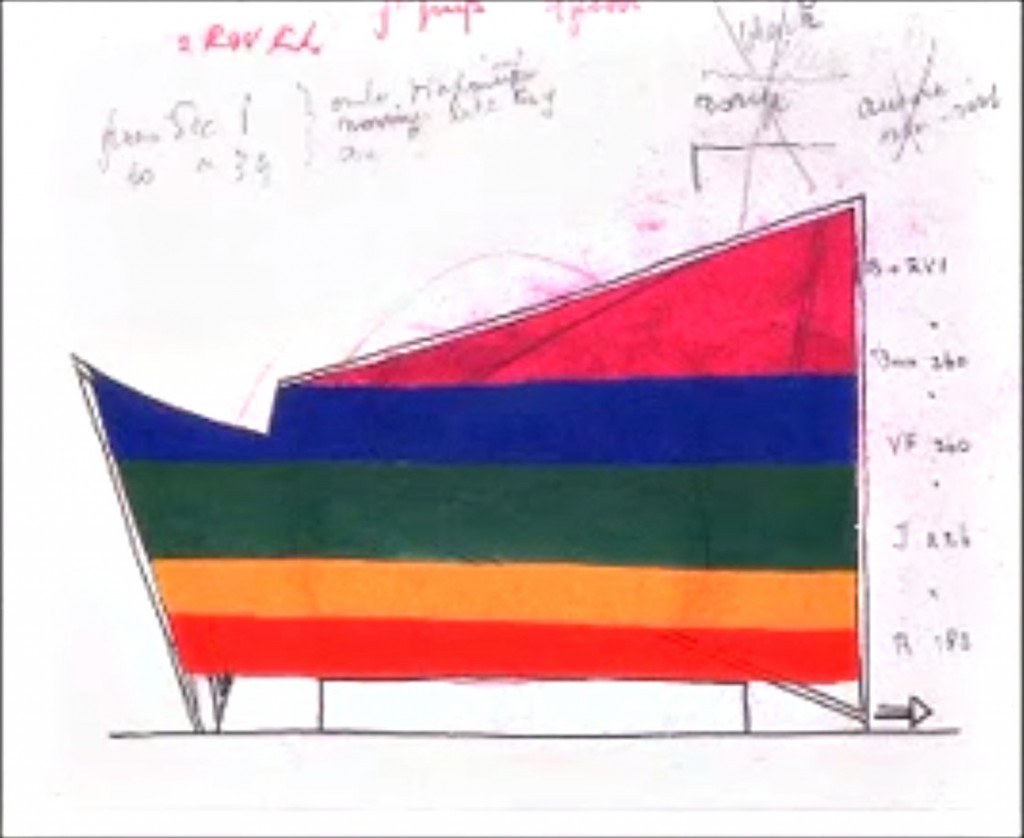

The interior of the pavilion was also lit by a constantly changing pattern of colored lights, and in addition to the film, three separate projectors showed additional still photos on the walls.

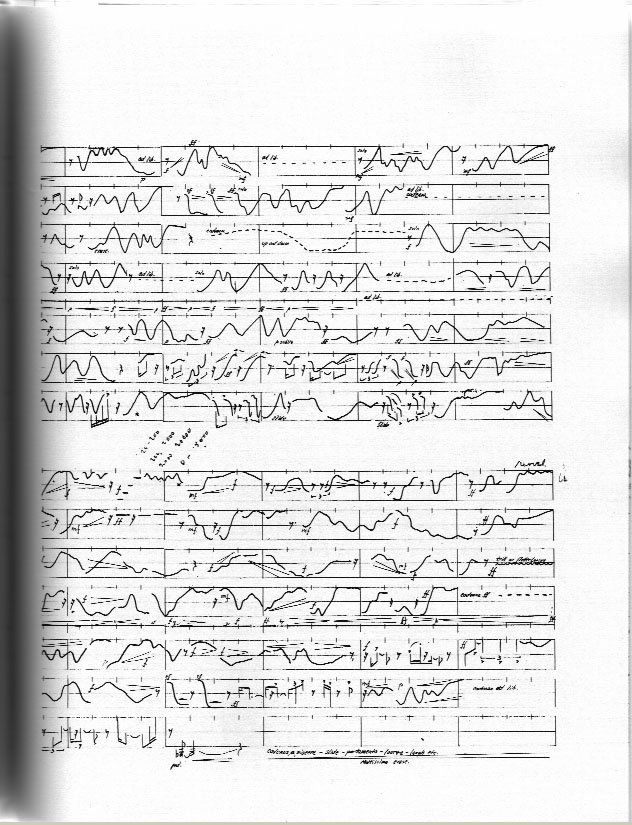

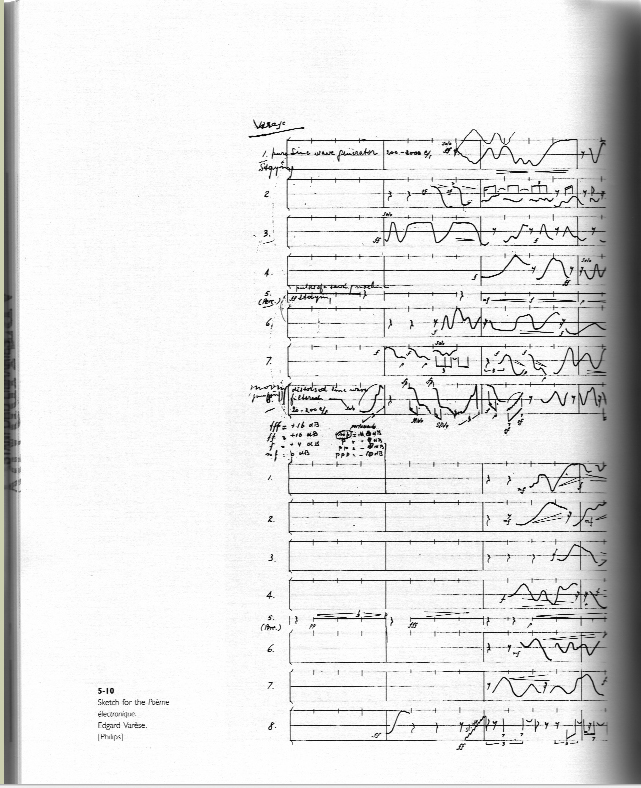

Spatialization

Varèse designed a very complex spatialization scheme which was synchronized to the film. Prefiguring the acousmonium style of sound projection, hundreds of speakers were controlled by sound projectionists with a series of rotary telephone dials. Each dial could turn on five speakers at a time out of a bank of 12. Many estimates of the pavilion’s sound system go as high as 450 speakers, but based on the limitations of the switching system and the number of projectionists used, an estimate of 350 seems more reasonable. The speakers were fixed to the interior walls of the pavilion, which were then coated in asbestos. The resulting appearance was of a series of bumps. The asbestos hardened the walls, creating a cavernous acoustic space.

The spatialization scheme exploited the unique physical layout of the pavilion. The speakers stretched up to the apex of Le Corbusier’s points, and Varèse made great use of the possibilities, sending the sound up and down the walls.[1]

Recording

The piece was originally recorded on three separate mono tapes, two of which were in turn recorded onto a stereo tape with panning effects. The stereo tape and the remaining mono tape were finally combined onto 35-mm perforated tape in order to synchronize the tape with the film and lighting changes.[2]

Sequence of events

The images in Le Corbusier’s film are all black and white still photographs and willfully abstract. The first image is a bull’s head in a spotlight. The final image is a woman holding an infant. Le Corbusier assigned thematic sections to the film:

| 0 – 60″ | Genesis |

| 61 – 120″ | Spirit and Matter |

| 121 – 204″ | From Darkness to Dawn |

| 205 – 240″ | Man-Made Gods |

| 241 – 300″ | How Time Moulds Civilization |

| 301 – 360″ | Harmony |

| 361 – 480″ | To All Mankind |

The sequence of sounds in Varèse’s composition:

| 0″ | 1. | a. | Low bell tolls. “Wood blocks.” Sirens. Fast taps lead to high, piercing sounds. 2-second pause. |

| 43″ | b. | “Bongo” tones and higher grating noises. Sirens. Short “squawks.” Three-tone group stated three times. | |

| 1’11” | c. | Low sustained tones with grating noises. Sirens. Short “squawks.” Three-tone group. 2-second pause. | |

| 1’40” | d. | Short “squawks.” High “chirps.” Variety of “shots,” “honks,” “machine noises.” Sirens. Taps lead to | |

| 2’36” | 2. | a. | Low bell tolls. Sustained electronic tones. Repeated “bongo” tones. High and sustained electronic tones. Low tone, crescendo. Rhythmic noises lead to |

| 3’41” | b. | Voice, “Oh-gah.” 4-second pause. Voice continues softly. | |

| 4’17” | c. | Suddenly loud. Rhythmic percussive sounds joined by voice. Low “animal noises,” scraping, shuffling, hollow vocal sounds. Decrescendo into 7-second pause. | |

| 5’47” | d. | Sustained electronic tones, crescendo and decrecendo. Rhythmic percussive sounds. Higher sustained electronic tones, crescendo. “Airplane rumble,” “chimes,” jangling. | |

| 6’47” | e. | Female voice. Male chorus. Electronic noises, organ. High taps. Swooping organ sound. Three-note group stated twice. Rumble, sirens, crescendo (8 minutes and 5 seconds).”[3] |

bronnen

https://www.youtube.com/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5a62bF50oIA

https://ccrma.stanford.edu/CCRMA/Courses/154/Varese%20images.html: All images were scanned (some quite badly!) from Space Calculated in Seconds, by Marc Treib and Richard Felciano (Princeton University Press, 1996).

1 Joe Drew, “Reconstructing the Philips Pavilion”, ANABlog, January 2010.

2.Vincenzo Lombardo, Andrea Valle, John Fitch, Kees Tazelaar, Stefan Weinzierl, Wojciech Borczyk, “A Virtual-Reality Reconstruction of Poème Électronique Based on Philological Research”, Computer Music Journal, Summer 2009, Vol. 33, No. 2: 24–47.

3. Roger Kamien, “Music: An Appreciation”. page 528. Copyright © 1988, 1984, 1980, 1976 by McGraw-Hill.